home

previous archive

September 1. I recently noticed that my favorite Bible verse is basically the same as my favorite song verse. From Ecclesiastes 9:7, "Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works." And from Big Blood's Go See Boats, "You've got some fun, speak your own. Creation without us untying to your bone. Promise in this day time, do your things."

September 5. For Labor Day, I'm thinking about the word "work". One definition is very broad. Work doesn't have to be productive, because Sisyphus rolling a rock up a hill, that always rolls back down, is doing work. It doesn't have to be physical, because chess players thinking about their next move are doing work (and burning a lot of calories). Even meditation could be called work, when the literal intructions are to do nothing.

Another definition is narrow: in the context of a society where tokens are exchanged for goods and services, you're doing a service in exchange for some of these tokens. If you're reading an article about "work", this is usually what they mean, and if you practice reading "work" as "work for money", you'll see the subject more clearly.

Humans like to do stuff. But as a means for arranging the stuff we do, wage labor has only been common for a few hundred years. It is now in decline for multiple reasons, but the main one is that it's failing to satisfy our need for meaning, for our actions to be part of something larger that we believe in. We no longer believe that doing wage labor with more intensity (working hard) will make us rich. Employers are openly calling workers "resources" in their quest for higher stock prices.

In response, the phrase "work-life balance" frames wage labor in opposition to life. Back in 2004, when I wrote "How To Drop Out", people would say, what would happen if everyone dropped out? That's basically happening now. When I go to the drug store, and half the shelves are empty, I can't complain, because filling those shelves requires a long string of shitty jobs.

It's anyone's guess how it will all shake out. I like to think we're still in the early stages of figuring out how to run an ethical society. For the last few hundred years, the organizing principle of people doing things has been how much money can be made by people doing things, where money is the power to make people do things they would not do except for the money. In a better society, the organizing principle of people doing things is what people enjoy doing.

September 7.  Last week there was a cool post on the Psychonaut subreddit. The images on the right were generated by an AI, from this Terence McKenna quote:

Last week there was a cool post on the Psychonaut subreddit. The images on the right were generated by an AI, from this Terence McKenna quote:

This AI that is coming into existence is, to my mind, not artificial at all, not alien at all. What it really is, is: it's a new conformational geometry of the collective Self of humanity.

Now, I don't know what "conformational geometry" means. It sounds like a fancy way of saying form or shape. But I think he's right. The best way to think about AI, is to think of it as human. AI will never go rogue, or "become sentient". It will always do exactly what humans tell it to do -- which will never be quite what we want it to do, and increasingly, not what we expect. But it remains fundamentally an extension of our own story.

Meanwhile, here's a comment thread on the Seattle subreddit about something that's actually non-human, the intelligence of crows.

They see humans give other humans things and get food in return, but don't quite equate that only specific things count. I've seen them try to feed leaves and bits of paper to a vending machine before in hopes of persuading it to give up snacks.

September 12-13. Well-written article, Excuse me but why are you eating so many frogs, where eating frogs means forcing yourself to do stuff you don't feel like doing.

These were students who had eaten enough frogs to get into Princeton and Harvard. Their reward was -- surprise! -- more frogs. So they ate those frogs too. And now they're staring down a whole lifetime of frog-eating and starting to feel like maybe something, somewhere has gone wrong.

If we're deciding what kind of tasks to build our lives out of, there are three common answers: 1) do what leads to wealth and status, 2) do what you enjoy, and 3) do what you believe in.

I've been framing it in terms of enjoyment. That's not wrong, but this blog post, On being tired, mentions a framing I find more useful: tasks that give back energy vs tasks that drain energy.

The culture of motivational speaking assumes that your belief, your attitude, your aspiration are all-important. I think those things are like jump-starting a battery. Then, if doing the actual tasks doesn't give you energy back, your battery is going to die again. That's why I failed as a homesteader. Even though I strongly believed in self-sufficient low-tech living, it turned out that almost all of the actual tasks drained my energy. (The only one that didn't was throwing sticks into piles.)

Stripping it down even more: the word "motivation" points to two different things, which I'm calling aspiration and feedback. Aspiration is how good you feel about doing the task, before actually doing it. Feedback is when you do the task, how much that makes you feel like doing more of it.

My hypothesis is, there is little or no correlation between the two things. So being really excited about doing something, or not, tells you almost nothing about whether you'll be able to keep doing it, or burn out.

If I'm right, then the best life strategy is not to set a goal and sacrifice anything to achieve it. The best life strategy is to cast about trying a bunch of different things until you find what fits you.

September 20. The Problem with Intelligence. The article looks at a variety of things that word points to, and concludes:

Intelligence is always specific to the application. Intelligence for a search engine isn't the same as intelligence for an autonomous vehicle, isn't the same as intelligence for a robotic bird, isn't the same as intelligence for a language model. And it certainly isn't the same as the intelligence for humans or for our unknown colleagues on other planets.

If that's true, then why are we talking about "general intelligence" at all?

September 26. Jupiter is closer today than it's been for 59 years. And I'm wondering, why are the clouds on Jupiter beautiful? More precisely, why does the human brain see beauty there? You could argue that humans find trees beautiful because they're part of our evolutionary environment (although it's hard to think of a survival advantage). But we could not have evolved to see beauty in anything that requires a telescope, or a microscope.

And yet, we see beauty in nebulae, in the rings of Saturn, in micro-photography of insects and beach sand. When you look around, almost everything in the non-human-made world is beautiful. I think we see that beauty because our brains and eyes are also part of the non-human-made world, and they share a kinship on a level we still don't understand. "The kingdom of heaven is within you."

So why is the human-made world so full of ugliness? This article, The Smartest Website You Haven't Heard of, is about McMaster-Carr, an industrial supply company, and how much better they are at e-commerce than Amazon. At the end, there are two interesting quotes. First, from engineer Dan Gelbart:

If something is 100 percent functional, it is always beautiful... there is no such thing as an ugly nail or an ugly hammer but there's lots of ugly cars, because in a car not everything is functional... sometimes it's very beautiful, if the person who designed it has very good taste, but sometimes it's ugly.

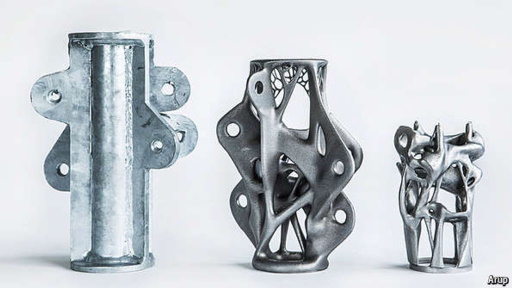

This image is from a 2015 article, Wonderful Widgets. The one on the left, though functional, is totally ugly. But the next two are more beautiful, and that beauty has been achieved purely by making them more functional.

This image is from a 2015 article, Wonderful Widgets. The one on the left, though functional, is totally ugly. But the next two are more beautiful, and that beauty has been achieved purely by making them more functional.

This is what I mean when I say that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature. Human civilization is still like the widget on the left, and in ten thousand years, it might be like the widget on the right.

So human-made ugliness doesn't just come from bad taste -- it also comes from clunky functionality. And I think there's a third cause. From the footnote on the McMaster-Carr article:

Jeff Bezos is an infamous micro-manager. He micro-manages every single pixel of Amazon's retail site. He hired Larry Tesler, Apple's Chief Scientist and probably the very most famous and respected human-computer interaction expert in the entire world, and then ignored every goddamn thing Larry said for three years... Bezos just couldn't let go of those pixels, all those millions of semantics-packed pixels on the landing page. They were like millions of his own precious children.

A lot of the human-made world is designed neither for functionality nor beauty, but for human social reasons, for status and ego. Consider the lawn. Lawns are both less beautiful and less functional than a lightly tended assortment of locally adapted plants. And yet, people spend massive time and resources on lawns, because lawns are a symbol of the cultural drive to impose control.

Our world will continue to be ugly until we change our culture, so that we feel better about allowing things to be good in their own way, than making them be the way we tell them to be.

September 29. Last Friday I did another interview, and it occurs to me: writing a blog post is like recording a song in the studio, and doing an interview is like playing a live show. My blog posts are carefully edited, and often patched together from things written at different times. Then when I do an interview, it's mostly stuff I've said on the blog, but it's all in one raw take.

Last month's Hermitix interview was the first I'd done in a while, so I spent hours preparing, and then I did it sitting down, over Zoom, on a USB headset.

This one I did with no preparation at all, on my phone, while pacing around the roof of my building. So it's more disjointed and headlong, but it's possible that I said more interesting stuff. Thanks Robert for the Ran Prieur Leafbox interview.

October 5.  In the Leafbox interview, I was asked "Do you have any religious practices?" I said no, but actually I do. Every year in June I take a long walk, with certain cognitive enhancements, in a good semi-wild area. This year I was too busy moving, but I've arranged to housesit for my stepmom, so I could come back to Pullman in October and take my favorite walk, up the south fork of the Palouse River out of town.

In the Leafbox interview, I was asked "Do you have any religious practices?" I said no, but actually I do. Every year in June I take a long walk, with certain cognitive enhancements, in a good semi-wild area. This year I was too busy moving, but I've arranged to housesit for my stepmom, so I could come back to Pullman in October and take my favorite walk, up the south fork of the Palouse River out of town.

Every time I do this, I get reminded of the same insight, and try again to put it into words. This time I thought of a line from Mike Snider: "It is effulgent, visceral, radiant, and absolutely void of any objectivity or subjectivity whatsoever."

It's God and heaven rolled into one -- but those are loaded words. I'm talking about something genderless, nonhuman, and mostly beyond our perception and understanding. "Nature" is how it appears to us. The world of wild biological life is our primary interface to the one real thing.

Then I see, poking out of that, some ugly building, and I have to wonder: What's the point of humans? Why did we go off on this strange and painful path of disconnection?

There are a hundred stories we could tell. We are a meaningless accident. We're here to spread life to other planets. We're here to bring the carbon to the surface and go extinct. We're baby gods learning to be world builders. We're remedial souls qualifying to rejoin the whole.

The idea I got, this time, is a variation on a common saying, "We are the universe experiencing itself." Sure, but the universe is already experiencing itself all the time. It doesn't need humans for that. What we can do, is see the universe in the third person. A tree knows what it's like to be a tree, but it doesn't know what it's like to look at a tree with eyes tuned for aesthetics.

On my walk I borrowed a hat with the slogan "The Last Frontier". The last frontier is not space -- it's us. Just as we send astronauts into space to see the earth, the mind beneath the earth has sent us into a headspace so isolated that it can look back at itself.

I got the feeling that our job is almost done. Within a thousand years we'll be gone, not through failure but success. Our birthrates will taper to zero as our deeper selves are like, "Humans, been there, done that." But I'm probably wrong. Our brains are so adaptable, surely they're good for more than one thing.