And yet, we see beauty in nebulae, in the rings of Saturn, in micro-photography of insects and beach sand. When you look around, almost everything in the non-human-made world is beautiful. I think we see that beauty because our brains and eyes are also part of the non-human-made world, and they share a kinship on a level we still don't understand.

So why is the human-made world so full of ugliness? This article, The Smartest Website You Haven't Heard of, is about McMaster-Carr, an industrial supply company, and how much better they are at e-commerce than Amazon. At the end, there are two interesting quotes. First, from engineer Dan Gelbart:

If something is 100 percent functional, it is always beautiful... there is no such thing as an ugly nail or an ugly hammer but there's lots of ugly cars, because in a car not everything is functional... sometimes it's very beautiful, if the person who designed it has very good taste, but sometimes it's ugly.

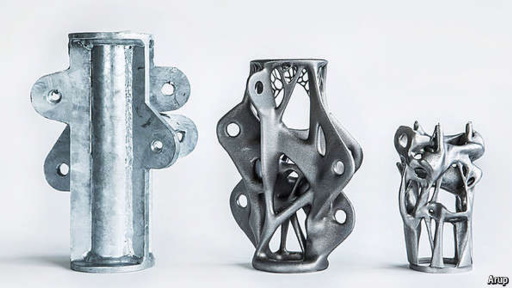

This image is from a 2015 article, Wonderful Widgets. The one on the left, though functional, is totally ugly. But the next two are more beautiful, and that beauty has been achieved purely by making them more functional.

This image is from a 2015 article, Wonderful Widgets. The one on the left, though functional, is totally ugly. But the next two are more beautiful, and that beauty has been achieved purely by making them more functional.

This is what I mean when I say that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature. Human civilization is still like the widget on the left, and in ten thousand years, it might be like the widget on the right.

So human-made ugliness doesn't just come from bad taste -- it also comes from clunky functionality. And I think there's a third cause. From the footnote on the McMaster-Carr article:

Jeff Bezos is an infamous micro-manager. He micro-manages every single pixel of Amazon's retail site. He hired Larry Tesler, Apple's Chief Scientist and probably the very most famous and respected human-computer interaction expert in the entire world, and then ignored every goddamn thing Larry said for three years... Bezos just couldn't let go of those pixels, all those millions of semantics-packed pixels on the landing page. They were like millions of his own precious children.

A lot of the human-made world is designed neither for functionality nor beauty, but for human social reasons, for status and ego. Consider the lawn. Lawns are both less beautiful and less functional than a lightly tended assortment of locally adapted plants. And yet, people spend massive time and resources on lawns, because lawns are a symbol of the cultural drive to impose control.

Our world will continue to be ugly until we change our culture, so that we feel better about allowing things to be good in their own way, than making them be the way we tell them to be.

Last week there was a cool post on the Psychonaut subreddit. The images on the right were generated by an AI, from this Terence McKenna quote:

Last week there was a cool post on the Psychonaut subreddit. The images on the right were generated by an AI, from this Terence McKenna quote: