home

previous archive

February 2. Reality by Consensus is a fascinating thought experiment, about what the world would be like if it filled itself in on the fly, based on our expectations and desires. I like to think reality is already like that, and for some reason we're all in a very sticky neighborhood. This subject reminds me of a quote from Terence McKenna: "It's a delusion if it happens to one person. It's a cult if it happens to twenty people. And it's true if it happens to ten thousand people. Well this is a strange way to have epistemological authenticity... We vote on it?"

February 4. So I'm finally reading David Graeber and David Wengrow's book The Dawn of Everything. This Goodreads review summarizes some of the main points, and this is how the book summarizes itself in chapter 1:

If humans did not spend 95 percent of their evolutionary past in tiny bands of hunter-gatherers, what were they doing all that time? If agriculture, and cities, did not mean a plunge into hierarchy and domination, then what did they imply? What was really happening in those periods we usually see as marking the emergence of 'the state'? The answers are often unexpected, and suggest that the course of human history may be less set in stone, and more full of playful possibilities, than we tend to assume.

The most interesting bit I've read so far is about how prehistoric people were able to move small physical items across continents, without capitalist trade networks. One way they did it was to invest the items themselves with great meaning. People made small works of art and went on long quests to trade them for other works of art.It's often said that money is the root of all evil, and then someone always points out that the actual quote is "Love of money is the root of all evil." Ironically, the motivation for making that argument, for defending money as not intrinsically harmful, is love of money.

Money is totally intrinsically harmful. Whether or not you love it, money strips the meaning from physical items, from blocks of time, from human activities, and replaces those many diverse meanings with copies of the same meaning: this is a token which can be used to force other people to do shit.

Graeber and Wengrow try to figure out why, in the indigenous societies of northeast America, material wealth did not confer the right to control others, while in Europe it did. I see it as a choice between two social paradigms. In one, you start with some concept of progress, and then force people to get behind it, and it becomes a war of all against all to climb out of the low positions into the high ones.

In the other, we start with the rule that no one shall be subject to anyone else's will, that the workforce shall be 100% volunteers, and then under that constraint, see what cool stuff we can do.

February 7. A "100% volunteer workforce" is my new way of describing the kind of society I want to live in. You could also call it "zero coercion" or "non-repressive" or "intrinsic" -- because everything that's done emerges from whatever people find intrinsically enjoyable. But I think "100% volunteer" gets to the heart of the difficult thing we're aiming for.

And yet, it's actually been done multiple times. And here, the worst move you can make is to look for some broad category that includes the societies that have done it -- whether you call them "primitive" or "low-tech" or "nature-based" or "indigenous" or "non-civilized" -- and argue that all we have to do is join that club, and we'll be happy.

On a practical level, that's just not true, and on an intellectual level, all the naysayers have to do is look through your category until they find one terrible tribe, and say, "Ha, you lose! Now go back to stocking shelves at Walmart."

A better move, which is made easier by Graeber and Wengrow's book, is to say, "The people who did that thing are human. We're human. So we can do it."

Now someone is going to point out that none of those people had airplanes or video games, and if we want the benefits of high technology, our society must force people to do stuff they don't want to do. I've found that it's not helpful to tell my adversaries what motivates them, but I'll say this: of all the reasons someone might choose to believe that high tech requires repression, love of high tech is not one of them.

Right now there are amateur enthusiasts in basements and garages doing all kinds of cool high tech stuff. On a practical level, we're a long way from making that culture the heart of our society. But there's general agreement that that's the direction we want to go. The most cynical corporate consultant knows that you can't brute-force creativity -- it comes out of social spaces with a lot of slack.

Going back to my January 31 post, about technologies needing the right context, Iphikrates wrote: "Plunk a fully functioning steam engine down in Bronze Age Mesopotamia and I guarantee you that absolutely nothing will happen." What we're aiming for is a social technology, in which you can plunk down a person whose spirit has not been broken, doing whatever they feel like, and they will find a niche that serves the system.

February 9. It's hard to imagine mining ever being done by volunteers. But now most of the mining has been done. There are plenty of reusable resources on the surface, or lightly buried in landfills. And picking through scraps for useful stuff is totally something people will do for fun.

In 2008, a guy tried to make a toaster from scratch, including smelting metal from ore. It turned out to be much easier to make a toaster out of parts of broken toasters. My point is, even if we get a deep tech crash, post-industrial technology will be radically different from pre-industrial technology.

Related: A makeshift submarine using IKEA food container and legos

February 11. Today's subject is mental health. A few months back, someone suggested that my emotional pain could be rooted in physical pain. I said, no way. Physical pain doesn't even bother me that much. I'd rather bash my shin on a table than feel anxiety, and I suspect that's why people cut themselves, to cover their inscrutable emotional pain with honest and real physical pain.

But now, after more self-observation, I see that it's true: emotions are rooted in the body, and when I'm in a bad mood, it's not from physical pain exactly, but general physical discomfort. Nine times out of ten, it's simple dehydration, and if I guzzle a quart of water and wait 30 minutes, I feel fine. It turns out that what I was calling "cannabis withdrawal" was a combination of dehydration and feedback: feeling bad about feeling bad. Now that I'm managing both, I can get high more often with no downside, although I'm still averaging less than one session a day.

In the past I've criticized "meditation", and I still believe that one specific practice -- sitting, focusing on your breath, and stilling your thoughts -- is overrated, and holds a monopoly over the vast range of metacognitive practices. Personally I do better walking than sitting. But any metacognitive practice is going to eventually pay off. More precisely, any way of building a perspective in your head that watches, in a curious and non-judging way, what your head and body are doing, is going to serve as a foundation for better mental health.

I've also found that the key is at the micro scale. If there's a way you want to feel all the time, the path is to feel that way now, in the thinnest slice of time, about the smallest thing.

February 14. For Valentine's Day, I want to write about "love". I put it in quotes because it's a classic propaganda word: everyone agrees whether it's good or bad (in this case, good) but nobody has a clear definition. We all know that it points to multiple things, and that the ancient Greeks had six words for it, but we mostly ignore that while throwing the one word around.

Specifically I'm thinking of people who have transcendent experiences, with or without drugs, and come back and say that love is the most important thing in the universe. I want to ask them how they would express that insight without using the word "love", but to give a good answer, someone would have to be really good with words. One of the few people who did a lot of drugs and was good with words was Thaddeus Golas. In his classic book The Lazy Man's Guide to Enlightenment he gave the best definition of love I've seen: "Love is the action of being in the same space with other beings."

I like how he defines it as an action and not a feeling. What I'm looking for is something that anyone can practice. But "being in the same space with other beings" requires some metaphorical imagination. It doesn't even make sense under materialist philosophy.

If I strip the word down to its minimum meaning, love is 1) feeling good 2) about something outside the self. That seems to leave out self-love, unless you consider that the subject and object of self-love are two different people inside you. As Nietzsche said, "Whoever despises himself still respects himself as one who despises."

I think what psychonauts are getting at is: the self is an illusion, and love is breaking that illusion so that being has no boundaries. But again, how does one practice that?

This is what I've come up with. Love is feeling good about placing your attention. It's not feeling good about the thing you're placing your attention on, because what about genocide? But even if it's something bad, you can still feel good about the action of touching it with your consciousness. The idea is, as you move your attention around, your attention is not dragging its feet, or stomping enemies, but dancing.

February 18-22. Crows may soon be Sweden's newest litter pickers. They're training the birds to pick up cigarette butts and trade them to a machine for food. Also in Sweden, plogging is a trend of jogging while picking up litter, which has since caught on in other places.

Personally, picking up litter is the one thing that I enjoy doing, and that society considers worthwhile, so I do a lot of it. And I'm surprised there aren't more people who do it. Scanning and picking up items is totally game-like, and the reward is something that most people want and never get: concrete evidence that you're making the world better.

What makes a person a litter picker or a litter dropper? My first thought is that we're all born litter droppers, because in our ancestral environment, everything is biodegradeable. But that's no excuse, because humans are also born learners, and even ants can learn waste management.

I understand how a person who is already mentally exhausted, would not want to devote a bit of their brain to tracking the location of something they no longer need. And yet, I find a lot of litter right next to trash cans. Related: many parks have reduced litter by removing trash cans, which puts park visitors in a mental state of having to pack their trash out.

It could also be about status. Dealing with trash might make someone feel lower, and knowing that someone else is going to have to deal with their trash makes them feel important. Personally, even if Jeff Bezos himself dropped a wrapper, I would not feel bad about picking it up, because I'm not serving Bezos -- I'm serving a place.

So litter happens when people feel alienated from their own locality. This has something to do with private property, a custom under which there are two kinds of spaces: spaces you personally control, and spaces you don't care about. But more generally, litter is a symptom of individual disconnection and social malaise, and right now it's a problem almost everywhere.

February 23. Mark Lanegan has died. He had a long career that I didn't keep up with, but he's my favorite Seattle scene singer, and I love his early stuff.

Nirvana's famous live performance of "Where Did You Sleep Last Night" is at least a fourth generation cover. First it was a traditional folk song called "In The Pines". In 1944, Lead Belly recorded this version, and in 1990 Lanegan covered that, with Kurt Cobain on guitar. Mark Lanegan's Where Did You Sleep Last Night is the Citizen Kane of grunge. A lot of what it did has since been done to death, but in 1990, this sound was mind-blowing.

That was on his solo debut, The Winding Sheet. The sound was mostly stripped down and acoustic, which was unusual at the time. According to Wikipedia, "Dave Grohl has called The Winding Sheet 'one of the best albums of all time' and has said that it was a huge influence on Nirvana's 1993 MTV Unplugged concert." It has no duds, and one song in particular has been stuck in my head all these years: Museum.

A month after that album was released, Lanegan was back with the Screaming Trees, and recorded one of the catchiest songs of the 90's, Bed of Roses.

He also turned out to be a good writer. From two months ago, this is an excerpt of his short book about almost dying of Covid. And from this 2020 interview, a quote: "If you want to do music, take any expectation out of it and do it for the pure love of it, you can't go wrong."

February 25-27. Some thoughts about Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Why is Putin crushing domestic dissent? Why doesn't he just do what we do in America, and let the anti-war protesters shout into the wind?

I see two possibilities. First, because of conditions in Russia that I don't understand, symbolic dissent will grow and grow until it becomes a full-on revolution and he's thrown out of power. I doubt that.

The second possiblity is that ignoring the protesters is the right strategic choice, and he's making the wrong strategic choice for emotional reasons. Domestic dissent really bothers him, and it makes him feel good to crush it.

I also think that's why he's invading Ukraine. Leigh Ann said yesterday, this is Putin's last chance. I said, "Last chance for what?" Surely not to serve the interests of humanity, or even Russia. It's his last chance to feel important by fucking shit up.

More generally, most of the aggressive actions throughout history make more sense as infantile rulers fucking shit up to feel important, than as anything thoughtful.

Of course, whatever we decide to do for emotional reasons, our thinking brain loves to rationalize it and take credit. And conspiracy culture is part of this cover-up. If you read conspiracist explanations of what any very powerful person is doing, it's all elaborate storytelling around the fundamental assumption that the elite are perfectly rational and highly competent.

I think powerful people are exactly as smart as ordinary idiots would be, if nobody ever told them they were wrong. Russia's invasion of Ukraine is not about the villainy of Vladimir Putin -- it's about the failure of dictatorship as a political system. What Putin is doing is just the usual stuff that anyone will do with unchecked power: veer off from reality, become paranoid and vindictive, overreach, kill a whole lot of people, and come to an ugly end.

March 1. I just read this in the book The Dawn of Everything. Among the Yurok, a tribe in northern California, there was a "requirement for victors in battle to pay compensation for each life taken, at the same rate one would pay if one were guilty of murder." There's no reason we can't have that rule in the modern world, except the continuing political influence of states that want war murders to be free.

March 4-6. Sad news from women's soccer. Stanford goalkeeper Katie Meyer, who made this wonderful celebration after stopping a penalty kick in a championship game, has taken her own life.

Whenever a highly successful person dies by suicide, I always wonder if the thing that caused the success, and the thing that caused the suicide, are the same thing. I can think of two habits that are correlated with both achievement and unhappiness. One is narrow focus, especially if you're zooming in looking for things that are wrong. The other is a get-things-done mindset. If life starts to feel like a video game where you've completed all the quests, then you need to re-imagine the meaning of life as something other than quest-based.

Anthony Bourdain once said this:

There's a guy inside me who wants to lay in bed, and smoke weed all day, and watch cartoons and old movies. I could easily do that. My whole life is a series of stratagems to avoid, and outwit, that guy.

If Bourdain had been satisfied to be that guy, would he still be alive? Maybe not, if being a celebrity chef was a way of running from something that was going to catch him either way.

Personally, I fight and fight to have nothing to do all day, and I always fail, because the world wants stuff from me. That's reason enough to not kill myself. The biggest reason is I have to finish my novel. But I think the most universal reason to keep living is the beauty of small moments. If you look for them, you can find them all over, and think to yourself, I'm glad I'm still here to see this.

March 7. I'm thinking about the difference between Russian and American propaganda. What all propaganda has in common is, it's always what you expect. Putin is never going to say, "Oops, those Ukrainians are tougher than I thought, and my military has terrible morale, so now I have to piss off the world by bombing Kyiv to rubble." Everyone knows he's going to say, "It's all going according to plan."

In America, and I'm thinking specifically of 24 hour news, they really try to get the facts right. Then, given the rule to not say anything false, they craft exactly the narrative that you expect. First they correlate the little views to make a simple big view, and then they show only the little views that match it. How much footage are they filtering out, not to hide some sinister truth, but to hide the fine-grain complexity of reality itself?

In a better world, mass audiences would be trusted with surprising details, like a happy refugee or a pessimistic soldier. But America still has more sophisticated and more effective propaganda than Russia. And this is not exactly about authoritarian vs non-authoritarian systems. The USA is still more top-down than bottom-up. It's just that we have enough bottom-up mechanisms that the rulers can't be ham-fisted.

March 10.  It may seem that sanctions on Russia are based on ethics, that we're making economic sacrifices for ideals. But a lot of ethical decisions are just non-short-sighted practical decisions. The reason so many countries are coming down hard on Russia, is that the world is poised to get more dangerous, with climate catastrophes and resource shortages looming. And in that global environment, the last thing we want is countries invading each other willy-nilly.

It may seem that sanctions on Russia are based on ethics, that we're making economic sacrifices for ideals. But a lot of ethical decisions are just non-short-sighted practical decisions. The reason so many countries are coming down hard on Russia, is that the world is poised to get more dangerous, with climate catastrophes and resource shortages looming. And in that global environment, the last thing we want is countries invading each other willy-nilly.

Maybe we'll fail, and by 2050 there will be wars all over. After WWI they tried to make a League of Nations to prevent another war, and of course that didn't work. But it had never been tried before, and I think we're getting better at it.

It's funny how certain combinations of words can take on meanings far beyond the meanings of the words themselves. If someone says "New World Order", what they're saying is: I fear a society coming soon, which will be 1) global, 2) repressive, 3) planned, and 4) stable.

I don't fear that, because you can't have all those things at once. It's hard to even have two of them. The trend, at this juncture of history, is almost the opposite: 1) balkanization, 2) more attention to human rights, 3) more need for improvisation, and 4) rapid change.

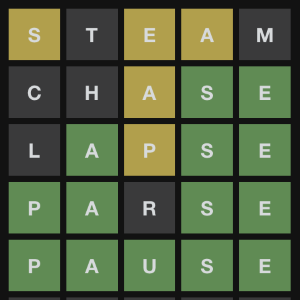

The old-school authoritarians are playing chess, and the rest of the world is playing Wordle. Chess is a steady marshalling of forces toward a clear objective, in which a single mistake can be fatal. Wordle is a series of wrong answers on the path to a right answer that you don't even know until you get there.

March 13. I like to write about the far future being better, because the near future is going to be a total shitshow. The other day I said that it's hard for a society to be two of these things at once: global, repressive, planned, and stable. But when I think about it more, two of those things are a natural fit: repressive and planned. The two that are hardest to combine are global and any of the others.

If we survive another million years, I don't think there will be a global government even once, because the things that government does are better done regionally. Also, something I learned from The Dawn Of Everything is how much humans love to differentiate themselves from other humans.

The best case would be what Leopold Kohr imagined in The Breakdown of Nations: thousands of diverse autonomous states, each made up of a city and the farmland around it. More realistically, we could have pretty much the nations we have now, with well-enforced global consensus about what a nation can and can't do. Like, no slavery, no killing protesters, and no invading each other.

If we can just get that one rule, no military invasions, then the door is open for all kinds of good stuff. Because right now, if a small nation does something that clearly works better, then a large nation, so as not to lose face, can just invade them to cover it up. But when good practices can't be crushed, they will eventually spread.

March 15. Smart article about car crashes during the pandemic. In the USA, "2020 saw the biggest single-year spike in traffic deaths in a century," while in Europe, "as driving went down, crashes went down."

The idea is, American roads are designed not for safety, but for speed and volume. The main thing keeping crashes down is congestion, which forces drivers to go slow. Remove the congestion, and the roads become deadly. And when the media reports on this, they generally ignore road design and focus on psychology. Instead of looking at the failure of roads to stop people from driving dangerously, they look at the failure of individuals to stop themselves from driving dangerously.

This is a theme I covered in this post last summer: societal failures framed as personal failures. Another example is obesity, which is caused by some new factor, maybe PFAS or lithium or linoleic acid, throwing off our intuitive sense of how much to eat, and forcing us to count calories to stay thin.

In a perfect society, no self-control is necessary, and right now we're about as far from that as we can get. We're all exhausted from constantly forcing ourselves to do the opposite of what we feel like doing, and meanwhile judging anyone who isn't as good at it as we are.

Back to car crashes, the Hacker News comment thread has some discussion about the word "crash" vs the word "accident", and a link to this page,

Crash Not Accident:

Before the labor movement, factory owners would say "it was an accident" when American workers were injured in unsafe conditions.

Before the movement to combat drunk driving, intoxicated drivers would say "it was an accident" when they crashed their cars.

Planes don't have accidents. They crash. Cranes don't have accidents. They collapse. And as a society, we expect answers and solutions.

Traffic crashes are fixable problems, caused by dangerous streets and unsafe drivers. They are not accidents. Let's stop using the word "accident" today.

March 23. There's a valuable concept in the book The Dawn of Everything, called schismogenesis. The idea is, people like to choose their values and behaviors, not so much from practical needs, as from the desire to be different from other people. This is why identical twins raised together end up more different than if they're raised separately; and it's why two neighboring tribes, in basically the same ecosystem, might have different cultures and even different diets.

This makes sense for the survival of the species. If one year there are no fish, or no tree nuts, then one of the tribes will still eat. But for your personal survival, and mental well-being, sometimes you have to recognize the urge to stand apart and overrule it.

There's a recently coined word, edgelord, which I would define as someone with the habit of believing or saying things that are provocatively untrue, so that they can distinguish themselves from other people, typically on the internet. The internet has buffed the power, the speed, and the danger of the schismogenetic urge. Flat earthers are the perfect example of people showing off their own ability to ignore evidence in order to make their lives more meaningful, but at least they're not doing any harm.